Juan Rodriguez Rock Journalist Legend and Pop See Cul zine

Juan Rodriguez is Montreal’s most esteemed, even legendary, rock journalist. He began writing about the music he loves in the early 1960s while in high school, publishing one of the first local music fanzines, Pop-See-Cul, from 1966 to 1970. He has written countless articles about music ever since, for the Montreal Star, Montreal Gazette and many others.

It was an honour to have him spend an afternoon at Archive Montreal in the spring of 2016, flipping through extremely rare copies of his own Pop-See-Cul and other vintage Montreal magazines, and giving us the back-story as only he could. We also spoke of his time growing up in 1950s Montreal, among many colourful anecdotes such as his encounters with Frank Zappa, Janis Joplin, the young Rolling Stones and local rock god Michel Pagliaro. The conversation included Archive Montreal co-founder Louis Rastelli, local music expert Alex Taylor and Juan’s longtime friend and collector, Drew Duncan.

JR: Juan Rodriguez

LR: Louis Rastelli

AT: Alex Taylor

DD: Drew Duncan

JR: I was born in England in 1948, and we came over here when I was five. You see, in 1953 they still had war rations in England. I had two sisters and my parents basically said, we cannot live on war rations. It was, like, one egg a week. Even though they had won the war, eight years afterwards, they still had rations! So my father got a job at the BBC international service, in the Spanish section in London. He eventually rose to become the head of the Spanish section … My father had a great voice, a very stentorian voice. He had made a movie in England with Noel Coward, who was the star, and he played the Spaniard. And while he was doing that job he had a second job as a ticket-taker at the racetrack. And my father was a bit of a gambler too, so… My mother wasn’t too pleased with that. But every week or so, he’d come back with a pile of money– but you know, nobody wins at gambling. At any rate, very soon after coming to Montreal, my father met Sam Gesser, who was the Montreal representative of Folkways Records. Sam got my father to do readings from Cervantes’s Don Quixote, and poems of Garcia Lorca for Folkways albums. (And they’re still available, if you write to the Smithsonian they’ll make a CD for you.) My father would also give readings, I remember my first visit to the Gesù Theater was for a reading. Sam wanted him on tour in the US because of the large Spanish population, and my father for some reason didn’t want to do it. He had a sort of lack of ambition. Sam was kind of upset because he thought that my father could succeed there. He was a lovely man, Sam Gesser, fantastic guy. Now I’m friendly with his widow, which would be his second wife, Ruth.

LR: Did your dad ever cross paths with Allan Lomax at the BBC?

JR: I think the family met Allan Lomax once. I heard he’d gotten music from Spain and all these other countries in Europe after being chased out for avoiding the commie witch-hunts in the US…

LR: We were just talking earlier, my speculation was that your dad would’ve been in the Spanish Civil War…

JR: Yes he was, and he used to tell us some horrific stories. My father fought on the good side, but he got imprisoned twice, and the second time he managed to escape to France and he joined De Gaulle’s free forces, then went on to England. In 1960, my father won an award in Spain called the Ondes Award for voice, and for the first time, under Franco, he had multiple assurances that nothing would happen and went to get the award. That was the first time I had ever been in Spain.

LR: Did he ever hang out at the Spanish Club?

JR: He certainly did, much to the chagrin of my mother. And sometimes he would do the trifecta; Blue Bonnets, Spanish Club, cognac, etc… That was where a number of Quebecois people like Claude Péloquin that hung out there.

DD: What street did you live on in Cote-Des-Neiges, by the way?

JR: The first place was on Dupuis Avenue. Then about a year or two later we moved to Van Horne Avenue, 5393 Van Horne.

LR: The Côte-des-Neiges area, I’m presuming was like it still is now, a landing-pad kind of place for immigrants…

JR: No, Van Horne was Jewish, we lived in that part, sort of before Côte Saint-Luc began (and many of them moved there afterwards). When we lived there, Côte Saint-Luc was just a huge, huge park. That’s where we used to play as kids. You would walk straight down the end of Van Horne and suddenly you were in the woods.

AT: This is also before the Decarie Expressway right?

JR: Yup.

AT: That was convenient for your father I guess, with the Blue Bonnets racetrack not too far…

JR: That’s exactly right (laughs).

AT: Were there any places for young people to hang out along Decarie back then, anywhere to see shows?

JR: Not that I know of.

LR: You would have been too young to see performers at Ruby Foo’s and that whole strip…

JR: Oh, I knew that whole area for sure. I was often the only non-Jew in our class, West Hill High School was 96 or 97 percent Jewish, so whenever they had Jewish holidays I had days off. I was class president twice in a row. There were three people in the running and they were all Jews, and one of them was Corky Laing. He was in my class, a very go-getter guy…

AT: Was he already drumming back then?

JR: Oh, yeah.

AT: Did you stay in touch?

JR: Yeah, when I was on the gig for The Montreal Star, I did an interview with Corky.

At the time I was in high school, JB and The Playboys was the group from Montreal. The Haunted were the quote-unquote “underground” band but JB and The Playboys actually had chart hits. The first Montreal chart hit was by The Beau Marks who did “Clap Your Hands.” That was 1960 or so, it had a bit of a regional US following.

LR: When did you first catch one of these shows? I’m presuming it was a curling club show or something when you were like thirteen, fourteen? Was it after the Beatles on Ed Sullivan?

JR: Yeah, I was clued in to everything before Ed Sullivan because my mother would get The Observer from England…

LR: Did you ever get records mailed over from England?

JR: No, but I began to pick up their stuff locally. Of course you had to make up your mind in those days; Beatles or Stones. I was a Stones guy because I prided myself on being the first person in town to know what the Stones were all about. I rushed up to Queen Mary Boulevard, they had a toy store just west of Decarie, that sold records in back, and that’s where I got my records from. At that time, I got “Not Fade Away,” of course…

AT: That was the first one in Canada I think?

JR: Yup. But, what I really prided myself on is that I got the Phil Spector singles and I had almost the complete collection. For me Phil Spector was the producer because he created his own sound.

LR: Do you remember what radio station you were listening to?

JR: Well, you know, CKGM or CFCF. CFCF was The Dave Boxer Show, and CKGM was Buddy G; George Morris. In ’64, The Animals had “House of the Rising Sun,” six minutes long! Sometimes Dave Boxer would play the whole six minutes, other times they had a radio version. But Dave hated the song. He held a contest, “Why I Like The Animals,” and I wrote in this sort of scholarly article about the blues, and I won. I was sixteen. I was thrilled when Dave Boxer said “I still hate The Animals, but this was a very, very good paper …”

LR: Was that the earliest you started writing?

JR: I wrote for the high school yearbook. It was only in my last year of high school that I decided I should contribute something.

LR: You mean contribute to the school newspaper?

JR: We didn’t have a school newspaper. What I did do is cartoons, they were called Pop-See-Cul Cartoons. I would tack them up on the bulletin boards.

LR: The Play on words was your invention?

JR: Yeah, absolutely. And the French, they thought that the title of the magazine was a real hoot, I mean, geez. And I hadn’t a clue about Cul (meaning ass)… I thought it was just “Pop,” “See,” the eye, and the “Cul” as for culture. Pop-See-Cul, the play on words with popsicle.

LR: So you were about seventeen when you began putting out Pop-see-cul?

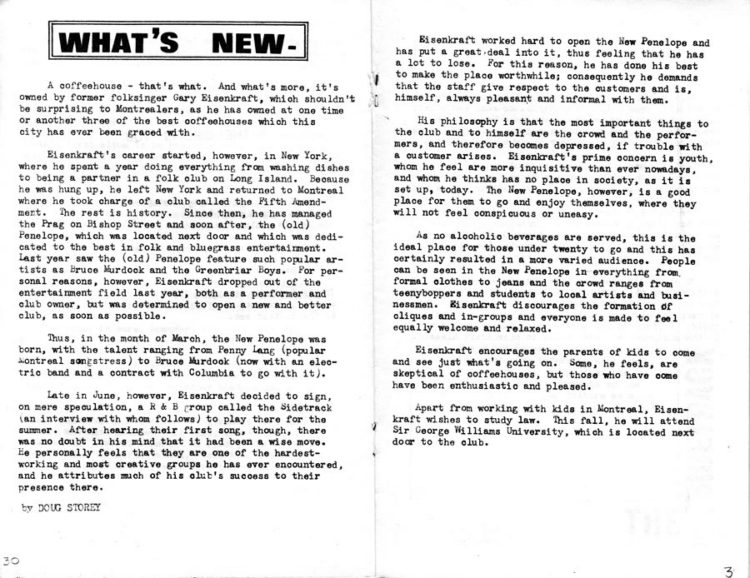

JR: Yeah. At the time, my mother wanted me to go to McGill, but my grades just weren’t good enough. I could get to Concordia, but not McGill. My mother, because of the snob thing, wanted me to go to McGill or nothing. She said, “Well, if you’re not going to McGill, you’re going to have to work.” So I found a job as a mail boy at the Montreal Engineering Company, which was directly opposite from the Montreal Star at that time. I kept going back and forth there, I would work six months there and then I’d quit, then I’d come back. I was the chief of the mailroom eventually. I printed the first couple editions of Pop-see-cul on their mimeograph.

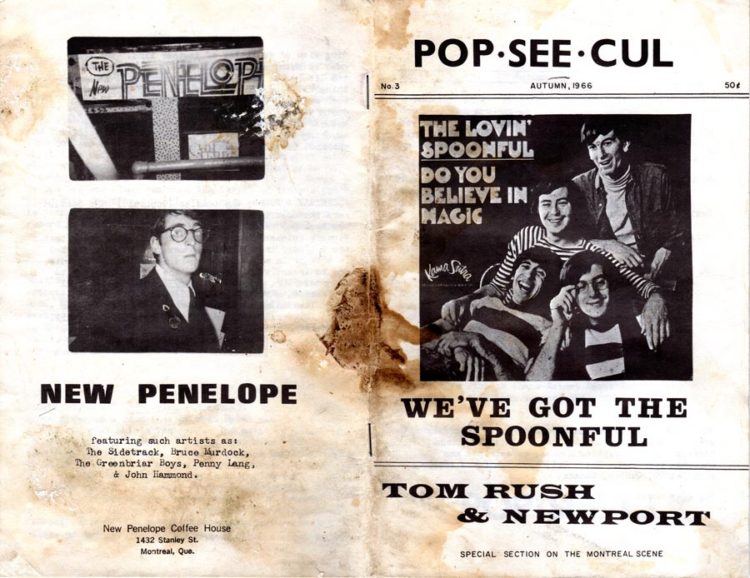

LR: That’s like the summer of ’66, isn’t it?

JR: Yup. It had The Lovin’ Spoonful on the cover.

LR: We got a copy from Francois Dallegret but it’s in rough shape. Is Andrew Cowan still around? Any of your old colleagues might still have copies?

JR: Andrew’s still around, he might have it. My mom might still have some in London.

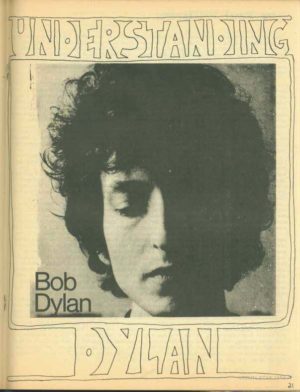

LR: This one says number three, autumn ’66. What inspired you to put out your own magazine?

JR: Everybody else was doing it. At one point we were like a member of the Underground Press Syndicate. It just seemed very natural, that was the thing that I wanted to do. You may have noticed I have a bit of a stutter, and it was terrible as a kid. Absolutely terrible. They’d laugh at me, and I’m convinced that that’s what made me want to write. I always had something to say.

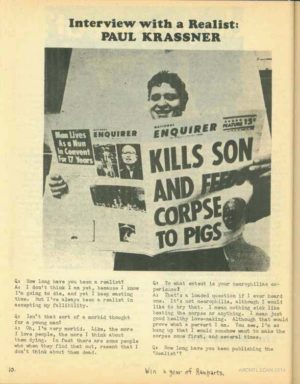

LR: This is more pop music than political…

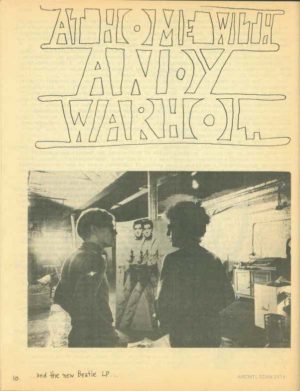

JR: But I liked to juxtapose pop type stuff with more serious stuff. We have an article by Buckminster Fuller… In this one you see Crawdaddy, which was the magazine of rock and roll started by Paul Williams, gave us one of Paul’s pieces in return for an ad. And then this here, I don’t know if you remember the hockey referee Red Storey? That was his son, Doug Storey. Doug was the odd guy out in the family, he was interested in music and all that stuff. And somehow he infiltrated himself with the Andy Warhol crowd.

AT: He didn’t take these pictures himself, did he?

JR: No, but they were lying around there and he picked them up, and there we go; “Exclusive!”

DD: Did you mention the other day that you found some of the Pop-see-cul content in an Andy Warhol Velvet Underground book?

JR: Yeah, the book that came out, I guess about two years ago. In the middle of it there was a copy of about six pages of Pop-see-cul, like a little collage, and Gary Eisenkraft had published that. It was funny because he promised us typesetting and managed to get a great deal from Monsieur Péladeau, because at that time, all Péladeau had was the Journal de Montréal, which had just started, because of strikes at Le Presse. So they were looking for business for the printing press. Gary printed four thousand of them and it was the biggest run that we ever had, huge, huge, huge. But unfortunately Gary wasn’t much of a distributor and they were left in a pile, most of them. We always went from store to store, you know, “Would you take this?”

LR: Metropolitan News?

JR: Yeah, Metropolitan News was the big one, but Classics Bookshop used to carry the Village Voice, and when we came out, they’d buy a whole pile. So anyway, he had these piles of magazines in his hallway. The apartment was on the third floor next to the Holt Renfrew building, where his girlfriend Melinda lived. They filmed The Ernie Game upstairs in that apartment, and there’s a scene, as you’re looking down the hall, and there they are.

AT: That’s why no one could find that copy, right? Because they’re all there.

JR: Yeah, it was a hoot. (Flipping through copies of Pop-see-cul): Here’s another article: Arthur Bardo was the art critic for the Montreal Star who moved here from New York. He was very rough on the art scene here, writing an article for Pop-see-cul called “Why High Art Never Got Off The Ground In Montreal.” That was him officially burning his bridges. There was also an open letter to Leonard Cohen by Robert Hirschhorn, who was a big publisher. Le Château was so upset about this ad here. Herschel Segal was the owner of Le Château and he supported the magazine. We actually had an office on Crescent Street, Sidney Rosenstone had a couple offices just above from where Ziggy’s is now. So we got this guy from New York who moved up to Montreal, Larry Schnitzer, and he was a very funny bonehead. We didn’t have any original art except for the Le Chateau logo, and so it was Larry who did this scrawl of the thing, and we went with it. Hershel was so angry.

LR: So he just didn’t like it, but then again, he told you to do whatever you wanted, didn’t he?

JR: Yup, he did. Then here’s Richard Meltzer, he’s famous for The Aesthetics of Rock.

LR: Did you republish this?

JR: No, that was an original article. Meltzer’s one of my greatest friends. Back in those days, you know, we had to lay the sheets out to collate them…

LR: Ah, we used to do that with my own zine Fish Piss from the 90’s, I think we were trying to do the same thing in different eras. Mixing politics with music and culture…

JR: Yeah, Fish Piss, oh wow, I read that…

AT: Did you ever see this magazine, Pop Cycle? I got this from Alain Simard, he told me the reason they chose this title, which was the first issue and only issue of this paper, was because of your paper Pop-See-Cul. And this was ’71, just when your magazine had basically come to an end.

JR: Isn’t that something, Pop Cycle.

AT: When he told me about that I said no, that can’t be right, he must be talking about Pop Rock Jeunesse…

JR: Well I did write a French article for Pop Rock, which was a tabloid like that, put out by Coco Jacques Letendre. He was a big music maniac, and I was able to get an exclusive music interview with Robbie Robertson. He had it in Pop Rock and I had my version in The Montreal Star. That was a whole story in itself. Robbie lived in the Côte-des-Neiges area, Jean Brillant Avenue, with his girlfriend Dominique. And he spent a winter here. We got together, she called me up at The Star and said that he wanted me to do an interview with him for a project that he had in mind. We went to this restaurant to talk about a movie on the Band’s roots and stuff like that. He wanted an article to help get Canadian funding for this movie, and they refused him. And that’s when he went to Hollywood for “The Last Waltz.” And Robbie, knowing that I had tried my best, invited me out to The Last Waltz for free. Everything was paid for by Capitol Records free of charge. I will always remember that concert which had everybody in it, Van Morrison, Eric Clapton, Joni Mitchell. I’d never seen so much cocaine in my life. It was just unbelievable. And you doubtless heard the story that Martin Scorsese had to rub out frame-by-frame a rock that was hanging from Neil Young’s nose. They had to do it by hand. And I remember going up the elevator with Eric Clapton, and Eric Clapton was just leaning up the elevator, just like that. It was terrific coke, by the way. It was fantastic. I remember Peter Goddard from the Toronto Star, we were the only two journalists there. I was in the room, you know, spread a little bit of coke down, and Peter had never tried it. He sniffs it up and then he goes “Ah-choo!” and there was coke flying everywhere … (Laughter). So that was the last time with Peter. At The Last Waltz I drifted up into the Cow Palace almost behind the stage, like looking down, and the only other person there was Michael J. Pollard from the movie “Bonnie and Clyde.” So we sat together, he had a little bit of weed, I had a little bit of coke, and we wordlessly did our thing, you know? And when Robbie saw me during rehearsal, I said “How’s everything going?” and he said “Well, it’s going pretty good, everything’s fitting nicely into the pocket.” (Laughs). That was the way he was. That was about the peak of the seventies. From my perspective, and I think I’m very correct in this, when The Beatles came, hit North America, the industry itself was not ready for it. They didn’t have enough pressing plants. They couldn’t handle the demand.

AT: You’re right, seems like whatever happened in the fifties did not grow the machine big enough, fast enough to accommodate the British Invasion.

JR: They kept hoisting out all the Bobbies on us: Bobby Vinton, Bobby Vee, all of them, and they had tried to arrest rock and roll, like they put Chuck Berry in jail, they had banished Jerry Lee Lewis because of the thirteen year old cousin. Fuck, who did the Beatles replace at number one? The Flying Nun. That’s what they foisted on us, you know? And so, boom! And then everything started accelerating very, very fast. We got the West Coast sound, we got the Boston sound, we had New York, The Velvets just got together, and it was in the seventies that the industry itself blew up into a monolith. And I think it was the age of the singer-songwriters, the first seeds of heavy rock, you know? And that’s what built the industry, like Carole King and all those people, one singer-songwriter after another, James Taylor, I couldn’t stand any of them. But it became a mega, mega, mega industry. And my friend Meltzer said basically rock and roll stopped in 1968. Everything after that was just hype and bullshit. And the hype machine was amazing. They used to buy journalists off. My first week on the job at The Star, I had written six freelance pieces for The Gazette, quite little pieces but I did the first Jesse Winchester article, that was the first time he was ever reviewed. After six had appeared, I finally called up the editor and said do you think I could get paid for this? And he said, “Oh okay, fifteen bucks a pop, chickenfeed.” That’s exactly the way; “Oh, thank you sir, thank you so much.”

DD: Now you’re a professional, right? When you get paid you’re a professional.

JR: Exactly. And then I decided to go to London in ’69, where the action was. I lived there for six months. At that time The Stones were getting rid of Brian Jones. I rang The Stones’ office and said “I’m here from The Montreal Star, can I do an interview with The Stones,” and they didn’t say no. The secretary said, “We’re going to have a major announcement coming up in a few weeks, let me put you on the list.” And sure enough, I was the international representative when they introduced and I went to their offices on Warder Street, and they introduced Mick Taylor, and that was the first time I interviewed The Stones.

AT: Did you know at the time that (Montreal singer) Nanette Workman was in London, that she had sang on “Honky-Tonk Woman”?

JR: And “Midnight Rambler” also.

AT: You were familiar that she had been in Montreal with Tony Roman and all those people?

JR: That’s right. I got to know Tony very, very well. What I said to The Star in March ’69 was “If I get you an interview with The Rolling Stones, will you hire me as a pop critic?” And they had no pop critic at that time. In hindsight, that’s when everybody started hiring a pop critic. When shows would happen they would get the theatre critic to write about it or the dance critic. And sure enough, I got hired in September of ’69. The first show that I reviewed was The Doors at The Forum and Jim Morrison was so fucking drunk that The Doors didn’t even stop between songs, they just kept rolling into the next one, get the show over with as quickly as possible. And I had to write the review, and the headline was “Doors Bore but Boppers Lap It Up.” Did I ever get mail!

AT: You must have received a lot of hate mail. I read reviews of Led Zeppelin, The Kinks, Bowie, and stuff, so, like those fans… The Kinks at the FC Smith auditorium in ’69 or ’70, and I was thinking, “That guy must have had a lot of enemies.”

JR: It was great, I was the guy that they loved to hate. And it was the hype that got me riled up about The Kinks, because The Kinks, for me right now, I prefer their stuff more than any other British Invasion group, period. It transcends the word “classic,” it is rock and roll, you know? And their early hits were fantastic, and then Ray Davies, when he started writing the social stuff dedicated to all the fashion, stuff like that, nobody had even touched him, as far as zeroing in on class, and all this kind of stuff. That’s why I always thought that The Beatles were totally overrated and I still believe that to this day.

AT: They weren’t writing relevant songs to people?

JR: The Beatles were a phenomenon, and there’s a difference between music and a phenomenon. They were an incredible phenomenon, they were an incredible catalyst, you can’t say enough about them. But as far as songs were concerned, first of all, I loved their covers of Motown stuff, but songs like “Please Please Me,” and “Love Me Do,” weren’t very substantial songs. And I always thought “Sergeant Pepper” was a piece of shit, apart from one song; “Day in the Life,” which I thought was a masterpiece. And what I’m beginning to see now in the polls, “Sergeant Pepper” was always the number one album, it was de facto, and in the last issue of Uncut Magazine, they had the two-hundred greatest albums of all time and “Sergeant Pepper” had slid to number twenty-one. So it’s on its way down now. “Rubber Soul” was good too. I’ll always remember a rainy night in Montreal, it was November ’65 when “Rubber Soul” came out, eh? And I went to Archambault, because Archambault had the record store, in Place Ville Marie, and I bought “Rubber Soul” and I bought Ray Charles and Milt Jackson “Soul Meeting.” Jazz and pop. And I felt so proud of myself that I could like the both of them equally. “Rubber Soul” was a very sophisticated album and very good. But, you know, at that time The Stones did much better stuff, “Beggar’s Banquet,” “Let It Bleed,” those are fantastic albums. There were no throwaways at all.

AT: Did you go to the first concert in ’65 at the Paul Sauvé?

JR: I certainly did. That’s when I met them. April of ‘65. My friend Simon Schneiderman and I decided to find out where The Stones were staying. Most of the hotels were along what was called then Dorchester Boulevard, and that was about it. But we hit the motel on the corner of Guy and Dorchester. And we had figured, well, you know, they’re not that big, as a matter of fact, in North America, they’re not that big at all. Their biggest hit to date was “The Last Time.” And we figured that they might be at this motel. We tried there, we said we’re looking for The Rolling Stones and the guy behind the desk had this really nervous look on his face, he said “No Stones here.” So, we said, “We’ve hit pay dirt.” We went around the corner and we went to the service entrance just as someone was walking in. And we figured, well what floor do you think they would be on? Probably the top floor. We went up to the top, and they had just arrived and we saw seven doors that were open. You know, like, bits of luggage. Five for The Stones, one for Ian Stuart who was the piano player and roadie, and the other one for Andrew Loog Oldham. Bingo, we hit pay dirt! We went in and chatted with every single one of them, thrilled. We got their autographs.

LR: Do you still have those?

JR: Well, the stupid thing is, I gave the paper with all five autographs on one single piece of paper, which must today go for huge sums, I gave it to my girlfriend.

LR: That’s not too bad, the guy from Logos, remember when he got the “Magical Mystery Tour” film from John Lennon, there was a note saying, “Here you go, good luck with everything, signed John,” so he chucked it in the fireplace right away. It was a different era…

JR: Well yeah, it is like a different era…

LR: They weren’t offended either by having you show up like that?

JR: No, they were fine with it. They were just fine.

LR: They were a bit older than you I guess at that point…

JR: Just a bit. I remember Mick was on his bed reading fan mail, Brian Jones had ordered a drink from the bar service and he took one taste of it and he said, “I said double, you idiot.” And he just kept on combing his hair, looking in the mirror. He was dressed to the nines with two-tone shoes. Bill Wyman was extremely loquacious, very, very nice guy. Did not look like the old stone-face, you know, very nice guy. Charlie Watts was just a little tired, and Keith was trying out his brand new western-style guitar. He had just bought it. And that was the first stop on that tour. And I’m told between Montreal and Toronto, that they wrote “I Can’t Get No Satisfaction.” I’ve been told that by a couple of sources. I’ve read all the accounts. Like I said to Keith while he was strumming, “Hey man, is this all real?” (Laughter) Like a real dorky adolescent. And he said, “Hey, we haven’t come this far without playing for keeps, mate.” Very confident fellow.

LR: Well, it was just really happening for them finally…

JR: What happened right after was “Satisfaction” was definitely a big hit.

LR: Do you think “Satisfaction” had something to do with the Montreal experience?

JR: I don’t know, I’m thinking maybe the ride from Montreal to Toronto wasn’t very satisfying. They had the Sauvé show and then when they came back in October, they were in the Forum, and that’s where the riot broke out. They had to close the lights, they tried everything in the book, girls screaming, rushing the stage like locusts, and it was really exciting. It was really, really something. And the shows that they gave in ’66, they’d come back every year. I was there for the 65 riot. It suddenly turned dark. Dave Boxer came on stage, “Kids, kids, we can’t go on like this,” but when you see pictures from the European concerts, particularly Germany and places like this, it was the same reaction. Kids jumping on the stage and mauling The Stones.

AT: So that’s what the “riot” was, it wasn’t in the streets afterwards, right?

JR: No. That was the riot inside.

LR: Did you go to many shows at Expo in the summer of 67?

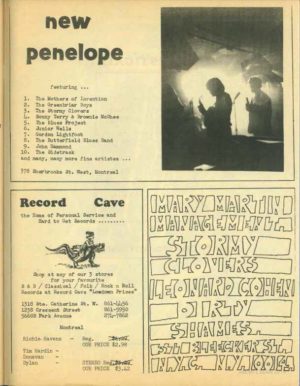

JR: At Expo I saw a lot of the shows, I saw Leonard Cohen there. Then I saw Leonard at the New Penelope as a spectator who was looking at Joni Mitchell. And I saw them walk out together. The rumour is true. I was there! I had first met Cohen through Gary Eisenkraft. I had published a book of poetry that I sold at The Record Cave. Cohen somehow was at Gary’s apartment one day and I handed him a copy. He looked at it studiously and says, “Hey man, this is really good.” So it was very encouraging. Early on Leonard was in an occasional country band called The Buckskin Boys, but I think the motivation that got him into music was when he saw Bob Dylan, and hitting the charts like crazy. He said “This is the way to make big bucks.” Because you don’t make any money on these poetry volumes. Maybe he’s made some money since on those, but it was a drop in the bucket compared to this huge record industry.

LR: He ended up at Columbia, the same label as well…

JR: Yup. He had the same manager, Mary Martin, that managed this band that used to play at The Penelope, The Stormy Clovers. And that was his in. That was his connection.

AT: I heard that they were the first band to actually record “Suzanne,” so he must’ve been like, “Oh yeah, I could go into this medium and do well with it without a band.

JR: Absolutely. The first review I did of him, I just totally slammed him. I remember it extremely well, it was at the Théatre St-Denis, I think it was 1970, and the mood was so reverent, sickeningly reverent– like along the stage they had put candles, you know, it was like going into St-Joseph’s Oratory except it was a show. And he had his country band with him, with Bob Johnson and the boys, I thought that he just droned and droned and droned. So my review was something like “It made me pine for Roy Rogers and Dale Evans to add some pep to this country music.” That time, he had stayed over in Montreal. There was this coffee place owned by Sidney Rosenthal on Crescent Street where Ziggy’s is now, and I got the word that Leonard wanted to meet me. That was right after the review, he was absolutely furious. So I walked in and he was there, saying “That wasn’t a review, it was gutter talk,” and I said, “Come on, Leonard, I thought it was kind of funny.” He says, “You know, my band’d like to beat you to a pulp.”

LR: Was he visibly angry?

JR: Visibly angry. He was trying to keep cool, but he was talking very loudly. Years later, he told me that he was so pissed off because his mother asked him, “Leonard, how come you’re getting so many bad reviews in Montreal?” (Laughter).

DD: Oh, just what you want to hear from your Jewish mother.

JR: And it was really only in 1988 when he put out “I’m Your Man,” when he embraced the electronic thing with those cheap synthesizers, I thought that was a great album, I still think it’s one of his best albums. That’s when I turned.

DD: You didn’t like his Phil Spector stuff? You’re such a Phil Spector fan.

JR: I like it, but I did an interview with him at that time and he said “I don’t know what to think about this album, it’s either a really great album or a really shitty album.” We got into the whole thing about Spector putting the gun to his head, waving the bottle of Manischewitz wine in one hand, as he drank and waved the gun around, making the musicians wait and wait and wait and wait. That was part of his secret, the musicians would be so on edge that when they finally got the word go, they would play their hearts out, just to get it over with. In a way I’m sure that’s what happened when Spector shot that girl, it became like Hollywood. He was probably playing around or something and, “Oops.” And Leonard tells me “Phil was saying, ‘Hey man, I love you’” And he said, “Oh, I sure hope you do, I sure hope you do, Phil, I sure hope you do.” (Laughter).

LR: Do you recall when “Suzanne” hit big, was there a sense of local pride?

JR: Oh, absolutely.

LR: Although it didn’t exactly lead to a whole lot of other local singers making it big…

JR: No, it was very, very difficult to imitate Leonard. I remember at the New Penelope, a guy that impressed me because he was so bad-tempered, was Gordon Lightfoot. And he played the original Penelope on Stanley Street. He had a very hardened face and I recall him as being very intense and very good. Not in that quote-unquote hippie-dippy intense way where every single word “means” something. Lightfoot had the very well-recorded songs, and it’s funny because, Bob Dylan, when he came out with that album “Self Portrait,” he had a couple of Gordon Lightfoot songs. “Early Morning Rain” was on that. Lightfoot, I think, has a sense of his own worth, he was sort of really pissed off to be playing in this tiny, little club and just wanted to get it over with. But, you know, he was a presence that I thought was quite something. I think he was frustrated at that point that he couldn’t get past Yorkville Avenue… People had to get into the States, had to break out of this limited Canadian market, and just finally get contracts and signings, management and all that stuff. So it would’ve been a step down playing, what was it, not even a hundred-person place?

DD: Were you too young to go to the earlier Eisenkraft clubs?

JR: Yeah, there was The Fifth Amendment. I saw The Lost City Ramblers, The Greenbriar Boys, Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee. It was just a kind of a “space,” today you call them a “loft space,” with a stage. Pete Seeger, I saw him, because my parents were in tight with the Gessers, we would get tickets to see Pete Seeger every single year that he came, and he always played the same venue, Her Majesty’s Theater, which is now the Guy Metro Station.

AT: The Fifth Amendment didn’t serve alcohol, did it …

JR: Right.

AT: From what I heard, Gary Eisenkraft, no matter what he tried to do, could never get a liquor permit…

JR: No, he couldn’t.

LR: Of course there were always places like the Swiss Hut to pop into for alcohol if necessary. What was the scene like there?

JR: You had separatists, lots of them; you had gadflies, like Nick Auf der Maur. And when Zappa came to Montreal for a two-week span in January of 1967, they were in the middle of this long residency at The Garrick Theater in New York, Gary Eisenkraft managed to book him at the New Penelope (next door to the Swiss Hut) for two weeks at the beginning of January ’67, and it was freezing. You can imagine all these people from L.A…. He wore this big raccoon coat, which of course was one of Zappa’s props, there’s tons of pictures of him in that raccoon coat, but that time he really had to use it to keep warm. Now, across from the New Penelope, there was a Banque Nationale, which is still there, and Zappa would ask me to come with him so that he could cash his checks.

LR: To vouch for him?

JR: Yeah, to vouch for him, that he was the real deal. And then they would retire to the Swiss Hut with Don Preston, Bunk Gardner, Jimmy Carl Black, they would go and have the breakfast or brunch. And I’d be able to sit there with them– I mean, Zappa was my hero, and still is… He was great composer of all kinds of music, and one of the great social satirists of the century. There’s no question about it.

LR: That was really early, around his first LP.

JR: Yeah and Frank told me very, very proudly that Freak Out was the first underground album that was distributed in Los Angeles supermarkets.

LR: Did you have that record when it came out, or did you know of them just reading through magazines…

JR: I had the record. Frank was very encouraging because I did a column at the time for the Sir George Williams University paper, now Concordia– even though I had dropped out, I still wrangled a column there once a week. I once wrote the same column for both The Georgian and the McGill Daily, railing against the New Left. Even though I am a leftist all the way, I didn’t like some of the tactics and stupidities that were going on.

LR: What about the Sir George affair, did you write anything during that?

JR: The famous computer riot. I wrote about that for The Montreal Star, editorial page. I did two pieces, and the first one was called Against the New Left. And some of my lefty friends — and I am a died-in-the-wool socialist, always will be — said “Juan, you shouldn’t have done that; it’s like writing an anti-Israeli piece in an Arab newspaper.” And I said, “Yeah, exactly.” (Laughter).

LR: I guess that was the real left, the hard left…

JR: Yup. Although once in a while they had good stuff. Ray Affleck, he was good. He was a leader I admired. You see, at the time there was the Quiet Revolution, you could actually see it– everything sort of bloomed, it was quite amazing. The skirts got shorter, the church began to have no influence at all. I do remember the fifties, and you could feel “La Grande Noirceur” (The great darkness), a sort of dark atmosphere of God and quasi-Nationalistic politics from Maurice Duplessis. Once he’d died and Jean Lesage came in, it changed overnight. The whole atmosphere. One of the flower children of that era would be Geneviève Bujold, she was in that movie with Yves Montand (The War is Over) and she was kind of a symbol of the generation. They used her singing in the soundtrack in The Devil’s Toy, about skateboarding. I had a friend who was in the movie, he gave me the background about all the things that were happening. It absolutely defined youth, that film. It’s so freewheeling, they’re skateboarding down Mount Royal, I mean it’s gorgeous, you know? And she’s singing and time is undetermined at that point. Ultimately it was about defying a city bylaw that prohibits skateboarding. So, all the fun that you have for youth only exists for a short period of time before the city outlaws it. When I was growing up, it was the pinball machines that were “a menace”. There was this one place on Monkland I went to, an ice cream parlor with pinball machines in the back. It only lasted for a year or two, and it’s because all the parents got together and said, “We don’t want our kids hanging out at this seedy place.” And then the mayor said, pinball is only permitted on St-Catherine St., to not corrupt the youth. It’s the same today, when you’re fifteen, sixteen, you know, going to places that your parents wouldn’t have appreciated you going to. It was no big deal back then going to clubs downtown when I was fourteen, fifteen. They would let you in, as long as you don’t make any trouble, and you don’t get all drunk and then throw up everywhere…

LR: I presume you behaved so as to see the concerts!

JR: Yes of course, sip my soft drink! But by 1967, it was the year of acid everywhere in Montreal and people were just walking around zoned out of their minds. I actually didn’t start taking drugs until I got to the Montreal Star in 1969, and even then, it was about 1970 when I started smoking pot, and 1973 when I started taking coke. And coke was definitely a huge seventies drug. And of course, with the coke, I started drinking. But in ’67, people were dropping like flies because of the so-called LSD overdoses, it was a big, big acid town. I remember one guy who published a magazine– he may have had something to do with Logos– he went to Afghanistan to pick up hash. He made sandals that were totally made out of hash, and there was a little bit of Afghan embroidery around it, and he’d walk through customs wearing them! They didn’t have drug-sniffing dogs that back then… Anyway, in ’67 there was a free concert with the Jefferson Airplane and the Grateful Dead right in the middle of Place Ville Marie. On this splendid property, architecturally and sort of monument-wise, it really signalled Montreal as a modern city. And it’s still beautiful. Whenever I pass it, it’s a beautiful thing. And you had all these freaks there, with these two groups at that time were number one and two of the west coast sound.

AT: Did you see any of the big Sam Gesser shows?

JR: Yeah, I saw one that he really regretted bringing in; Janis Joplin. I got an interview with Janis, and it was in an empty dressing room, just me and Janis an hour before the show. In those days, you could do things like that. And somehow, she walks in with a full bottle of Southern Comfort. I had never tasted it before and it was delicious. It was this nice, syrupy thing and we got through about three-quarters of the bottle, there was about that much left…

LR: Less than an ounce…

JR: Yeah, and she was having a high old time, hugs, and all this kind of stuff…

LR: Would you just take notes in those days for interviews?

JR: Nope, I had a tape recorder. And after the show, she tumbled down the stage, a big embrace, and says, “Man, gimme a good review, man, I die up there, I live and die up there, gimme a good review.” How could I not? She was very powerful, and she was very much in the moment. But what had happened before, and I heard this from Ruth Gesser is that the moment that she left the interview, a fan came up and she threw up all over him. (Laughter)

LR: I assume that would’ve been a sold out show…

JR: Yeah, well there was about eight thousand people there. They had her band, Full Tilt Boogie, and Ken Pierson (from Montreal) played keyboards. I went over to Ken’s place, not that night, another night, and he opens up his fridge and the entire fridge is just beer, that’s it. And I thought (goofy voice), “That guy’s really cool, man.” And he was a very, very nice guy,

DD: He played on “Pearl.”

LR: Does he still live in Montreal?

DD: He’s on the South Shore. We were just talking to him the other night. He said, “Boy if we’d only known, with ‘Pearl’ and Janis,” they had no idea that she’d become so iconic, or that the band would break like that. And look how fast it ended.

JR: Yeah, when she died, in one respect it was a shock, but in another respect it was, like, no surprise, you know? But I found her at that time much more beautiful than she was in pictures. She was really glowing, very scantily-clad underneath, long, long hair, the pimples didn’t really bother you…

DD: She was an authentic person…

JR: Yeah, she was. She wasn’t a looker, and when the Montreal Fine Arts Museum an exhibition on the sixties a few years ago, they invited her sister to come to lunch. Her sister was quite a bit younger, and she had the same build exactly. Really sexy hips…

LR: You think she looked like what Janis would’ve looked like without the drinking and the drugs? (Laughs)

JR: Yup. And I got the same feeling from Mike Hendrix also, because I saw Hendrix at the Paul Sauvé Arena.

AT: That’s with Soft Machine and…

DD: Our Generation opened for them I think?

AT: Olivus, Bruce Cockburn’s heavy band, he wanted to cash in on this sort of hard rock thing, that lasted about three or four months, and then pfft. Then he started his real career.

JR: Oh boy, I gave him a rotten review. (Laughter)

LR: Did you interview Hendrix when he was here?

JR: No, no, but I just saw the show and it was totally amazing. I also wondered how long he was going to last. I met The Beach Boys in Hotel Bonaventure in ’68, and at the time I was doing the occasional story for Hit Parader Magazine. I did about three articles, and one of them was with Carl Wilson. He was very, very disturbed at that time because he had to go into the army, and he didn’t want to, and he was going to declare himself a conscientious objector and he didn’t know how the other guys would relate to that. Would it screw their image up as an all-American band? He was very, very nervous about it. That was funny. I spent the night with The Beach Boys and half of the band, Dennis Wilson, I think Carl also, and they had some black guys who were backing them up, we were at the Queen Elizabeth Hotel, in the ballroom, they were doing their rehearsals, and it was the first time I had ever tasted heroin. Because there was heroin going around The Beach Boys.

LR: Wow, “Surf’s Up”…

JR: Had the heroin, snorted it up, and the moment I got out of The Queen Elizabeth Hotel, right in the outdoor lobby; “BARF!”

DD: That’s the second barf story today (laughs). Did you ever write for Circus by the way?

JR: Uh, huh… I got in through Richard Meltzer, and also Lester Bangs. I wrote on the Montreal scene for Creem Magazine. I wrote for all of them at least once. Fusion Magazine, I did Rolling Stone, that was the article on Jesse Winchester, I did English Rolling Stone in ’69 where I reviewed Nick Cohen’s book that became a movie of some sort. All of those magazines, Crawdaddy…

LR: Do you remember what the cover story was for Creem?

JR: Well, it was a piece on the Montreal scene. I tried to make a bit more cultural about the influence of French and the English, bla, bla, bla. And also, Richard Meltzer had a sidebar, because Richard would come up to Montreal every year, and then I would go down to New York every year. Richard did an interview with Mahogany Rush, and Tony Roman was there of course. Tony did the first Mahogany Rush album. And that was when Frank Marino was making the whole story up about being reborn as Hendrix, great gimmick. Then years later, Frank is whining, bitching and moaning, “This asshole Juan Rodriguez spread this story about me and Jimi Hendrix, that asshole.”

AT: It’s myth-building…

JR: Yeah, he knew exactly what he was doing, and he was good, he was really good. So I did all those magazines. Meltzer put out his own magazine, which was called Ajax, he printed it on the Xerox machines at Columbia Records, about a hundred copies each, they were quite thick. He printed an article that I wrote called “Neil Young’s Father,” about Scott Young. He was a sports journalist and he was Mister Toronto. Mister Upright. He even held his head up like that, Mister Upright couldn’t stand this rock and roll stuff, and when Neil’s amp blew he refused to pay for Neil’s new amp. Scott Young wrote a book called “Face Off” that became a Canadian movie and it was about a young hotshot who falls in love with a female rock singer, and suddenly in his rookie season, he’s burning up the league and this rock singer turns him on to bad habits. He gets benched and stuff like this, they’re in the playoffs, he goes on the ice, scores like crazy. In the meantime, his rock star girlfriend dies of an overdose. So he leaps onto the ice, “This one’s for her,” it was such a piece of garbage, you wouldn’t believe it. It was a failed critique of his son, obviously… I couldn’t stand Neil Young, and I still don’t like him very much… I still can’t stand the voice, I can’t stand the whining, “Helpless, helpless, helpless,” and “A maid, a maid, a man needs a maid,” I just found him so puerile and stupid, “Old Man” obviously about Scott Young. I just couldn’t stand him. And there was one show I remember, I would always watch the shows from the side of the stage, because I’m a little bit claustrophobic and I don’t like to have a seat right in the middle. So I watched Neil and his band come out, and they were absolutely stoned to the gills. Meanwhile some kid in front is saying, “Neil, Neil, Neil, can I have your autograph?” He was zoned out, would not acknowledge the fan at all, you know? That was a bad review. Another bad review I did was of Led Zeppelin.

DD: That was famous,

JR: I basically said you see the first ten minutes of them and you’ve seen the whole show, because it’s just constant repetition. They stayed overnight and they saw my review, and they went through the local CFCF Channel 12 and complained, and Channel 12 put them on the news! There was Robert Plant just wailing away about this review, (British accent) “This piece of shit man doesn’t know what he’s talking about!” (Laughter)

LR: You’re raining on their parade…

JR: Absolutely. Raining on their parade indeed. I’m told through a fan site that it was the worst review that they ever received.

LR: That’s a badge of honour, huh?

JR: That’s a badge of honour. Not long ago Robert Plant was in town with Alison Krauss for the Jazz Festival, and I met him in the press lounge. Now, I loved the album with Alison Krauss, I thought it was fantastic. And we were introduced, and I said to Robert, “That review that you got in Montreal when you first came here, that was kind of rough, don’t you think?” He nodded and I said, “Yeah, I wrote that!” (Laughter) And he smiled and he said (British accent) “Nice to meet you, glad that we’re still both hanging on,” it was kind of funny.

LR: I’ve been asking everyone we interview for this project for their memories of the mid 1970s, sort of a turning point and ending for the era that began in the 60s, especially with the election of the PQ in 76.

JR: I was on Mont-Royal on that Saint-Jean Baptiste Day just before the Parti Québécois came in. The fires were just raging, and of course we were fucking stoned out of gourds, weaving about– it looked like Dante’s Inferno! Multiple bonfires, people would put stuff in trashcans and set them off, boom!

LR: Were you there at that show, the infamous first time they sang Gens du Pays…

JR: Absolutely, I was at that show. You see, I’ve always been very sympathetic to the separatist cause, because I think that it is, de facto, a country with its own language. So I never had any qualms about separatism per se– the qualms I always had were how are they going to treat the Inuit, for example? You can only take a measure of a society by how they treat the “other.” And this was the big test. And I originally thought that the Quebecois would pass it; now I have my doubts. They’re kind of stuck with the “other.” It used to be the Haitian influx, but now it’s the Arab influx. And there’s less and less Pure Laine Quebecois.

LR: What about the Franco music scene at the time?

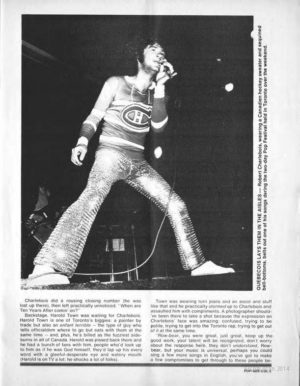

JR: Keep in mind that anybody who played during those ten or eleven years I was on the beat, I had to see them, no matter who they were. And it was three, four concerts a week. I reviewed Jacques Michel, I did Claude Dubois, everything. I didn’t understand hardly a word they sang, but they loved that the English were taking notice of their culture. They just loved it. It was definitely a big deal for them. I’ll always remember in 1973 when I got to know the Ville-Émard Blues Band, which was an amalgam of groups… one of them was Robert Charlebois’ backing band. Charlebois and the group were going to France for the first tour since Charlebois kicked in the drums at the Olympia, when the French called them “Les Sauvages d’Amérique du Nord” and so on. They were finally going back, and these guys from Ville-Émard, said “why don’t you come on over and meet us” at a certain town? We met near Geneva. Christian Saint-Roch was the drummer, a great drummer, he gave me a piece of dark Afghan hash, like that big…

LR: A softball?

JR: Yeah: “That’s for you, man, to enjoy the trip,” you know? And we went around France; it was like “The Magical Mystery Tour” you know? Had a lot of fun. I was the instigator, sort of, of getting that band together as the Ville Émard Blues Band. Very, very unwieldy, eighteen people, all these different styles. They did perform at the Théatre Saint-Denis to a packed house, but it was very difficult overall. Player’s cigarettes sponsored a Quebec tour, but they were an underground cultish type of band. I wrote the liner notes for their first album. I remember one of their fans was Robert Lemieux, the lawyer for the FLQ. And I remember after one of their shows at the Paul Sauvé Arena, they ripped out these planks of wood and we played hockey with a beer can, the referee was Robert Lemieux himself, the separatist lawyer. A lot of good times. I did a lot of drugs with them. The best mesc… And even in Paris, Bill Gagnon, the bassist, he was a wild, wild, wild bassist! Very, very good, I thought. He gave me some sort of sleeping pill for Paris, and he says, “Now, we gotta fight it. And if you fight it, if you fight it, you really get high, man!”

LR: If you don’t fall asleep…

DD: Can you talk a bit about your history and relationship with Pag (Michel Pagliaro)? Because I know you’re very good friends …

JR: I discovered him in the early seventies… I knew the English hits, then I got into the whole catalogue. He had a studio in Old Montreal, and he was getting this coke, it was just unbelievably good coke. We would talk all night, all night, he would play me tracks and tracks and tracks. He would come over to my place too, I lived on Atwater, stay the entire evening, and then be able to sort of drive home very quietly in his Cadillac, very calm. He was very, very hot at that time, hit-wise, spent many, many nights in the studio. I’ve often thought that he was best rock and roller that I’ve ever heard, actually, when he was in form. I thought that his last full album “Sous peine d’amour” was a beauty. Incredibly, incredibly good. But something about Pag, either he didn’t have the right management, or there was something gun-shy about him. He went out to LA, Meltzer met him, Meltzer adored him, was willing to do anything for him, and somehow the connections weren’t there. Now, I don’t know if it’s the mob or something, but the connections just didn’t happen. Those hits that he had, the English ones, “Some Sing, Some Dance,” “Rain Showers,” they were played on the East Coast radio stations. They were sort of cult hits, but they would get to, like number thirty-six, or number forty-two, and he had a base there and all the critics, all of my gang, the people that I knew, they loved him. “Give us more, give us more!” And it just didn’t come together for some reason. Why, I will never know. I’ll always remember, we went to a hockey game together in 1976, and this was the night that the Parti-Québécois won the election, it was Montreal versus the St-Louis Blues, but along the little strip there, where they had the scores running past, the vote tally was coming in every ten minutes. Pag, at the end of the hockey game, said, “Shit, man, it’s all over for me here. It’s all over.” And we said “Let’s go to Marty’s place,” Marty Simon, the drummer, he had a place on Stanley Street. Pag takes a huge bag of coke, I mean a real big, big baggie of coke, fantastic stuff, puts it on Marty’s coffee-table, and we wouldn’t leave until we had done the whole thing. And it was big, I can tell you. He feared a backlash because he wasn’t Pure Laine, and that was a really important thing in those days– you know, there were whole careers built on being a separatist artist.

LR: So you saw the big exodus?

JR: Yeah, sure, I mean, I did move to Toronto when The Star was on strike. I became involved in a couple of Canadian magazines, trade magazines.

DD: Political-wise, how did that feel? Being in Toronto back then, it’s like a weight that’s lifted off your shoulder…

JR: Well, I hated Toronto, I hated the lifestyle. I lived there because my friend Chris Haney who was co-inventor of Trivial Pursuit, he was a colleague of mine at The Gazette, and said “Give Toronto a chance, give Toronto a chance.” It was a tough time there and he said, “Juan, if you take this shit, you must really like it.” (Laughter) And he said, “I’m going anyway, but if you quit now, I’ll quit with you.” And I went upstairs, and I quit, but I gave them two weeks notice, and they had a security guard sitting right next to the desk and it was called “The Juan Patrol.” (Laughter).

Then as soon as The Star came back, I moved back.

LR: But then you realize you’re in Toronto…

(Editor’s note: The Montreal Star went bankrupt and closed not long after its strike, and Juan Rodriguez has written regularly for the Montreal Gazette ever since.)

Comments